- Home

- Sue Taylor

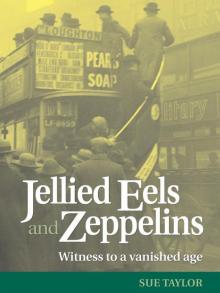

Jellied Eels and Zeppelins Page 5

Jellied Eels and Zeppelins Read online

Page 5

We never went to the fair - we just went for a walk. On Tuesday, when I went back to work, I spoke to a friend of mine, Lily, who seemed pretty reasonable, and asked her how she enjoyed her bank holiday. She replied ‘My friend and I went out and we went to the fair. And we met two fellas. We didn’t leave there ‘til gone five. We stung ‘em proper for money. And, do you know the field opposite?’ (There was this field opposite, you could walk through there and that used to bring you to the top of my road in Coppermill Lane, near the reservoir). ‘Well,’ she said, ‘My friend was waiting for the bus and the chap that was with me, walked me across the field and started taking liberties, so I hit him on the chin and knocked him out!’ (Lily was a Cockney, you know.) ‘Rotten devil - wanted to make us pay for the money he’d spent on us, I suppose.’ And then she asked ‘What did you do on your bank holiday Ethel?’

While I was telling her what had happened, I showed her a photo with Bobby in it. She said ‘That chap in the back row. Is he a friend of yours?’ ‘Yes,’ I replied. ‘Well, fancy picking someone like that,’ she said. ‘How do you mean?’ I said. ‘Well, you know that fella over the field? That was ‘im!’ When I told her that he was my fiancé, she said ‘Oh, I’m sorry, perhaps I made a mistake.’ But I said ‘No, you haven’t made a mistake, I have,’ and I packed him up straight away after that. I had my proof.

When Dad asked me why I had finished with Bobby, I said ‘I have my reasons. I’m not a child.’ Dad liked Bobby, and I’m sure that Bobby had told him a different story as to why we had broken up, saying that it was me who had been out with another fella, when in fact I had been out with a girlfriend one evening.

Dad wasn’t happy and accused me of cheating. We had an almighty row and I told him - and it was the first time I had ever answered my father back - ‘Don’t accuse others of what you did yourself!’ (I think he thought that I’d forgotten about his affair during the First World War). He went quiet and then I said ‘The way you’re speaking, it’s as if I wasn’t your daughter.’ And you know what he said? ‘Perhaps you’re not,’ and my mother sat in the armchair and sobbed her heart out. I’ll never forget that as long as I live.

I put my hand out to slap my father’s face, but stopped saying ‘No, I can’t ‘cos you’re my father.’ I turned to my mother and said ‘Look, I’m earning enough money to keep meself. I’ll get a place and you can come and live with me.’ But she said ‘I won’t leave my husband.’

I didn’t go out with anybody for about six months after that and then I met Joe, whom I was later to marry. He had got a job in the woodyard that was attached to Ensign and he used to ride a motor bike. He used to stack the wet planks of wood in special drying sheds or kilns as they were delivered, and made desks and dressing tables and all that. Before that, he worked as a builder making shop-fronts for the Co-op.

Well, I’d been out with Joe on his motor bike and he had just brought me home. As I got me leg over the bike to get off, I felt someone’s hands around me throat. It was Bobby. I didn’t know what to do, so I stuck me two elbows in his ribs and pushed ‘im off. He staggered a bit. Joe was facing the other way and, by the time he realised what had happened, Bobby had run off. He was a runner with the Essex Beagles and boy, could he run. Joe said that we’d race after him on the motor bike, but I was so shaken, I just wanted to go home.

Dad was having his Sunday afternoon nap, when Joe rang the doorbell and said ‘Look after your daughter, something’s wrong!’ He went after him on the bike, but Bobby must have caught the bus at the top of the road.

We reported the incident to the police and they warned Bobby never to interfere with me again. The copper was at the factory gates every day for a fortnight, but there was no more trouble. However, Bobby’s father was a boxer, and I did hear that he gave him a right telling off. After that incident, I had terrible pains in my stomach and was under the doctor for three years.’

Nine

Strikes, Frosts and a Total Eclipse

In May 1926 a General Strike was called and more than two million unionists stopped work in support of the miners. Ethel’s father, who was working for Lipton’s, came out in sympathy even though he did not belong to a union.

The strike lasted a mere ten days, but its effect on Edwin and his family was felt for much longer. For six months, their only income was that earned by his daughters.

‘Mum added a bit extra by making and selling her paper flowers, like the ones she made for Florrie and I at the Peace Tea at the end of World War I. I’ve still got the button hook she used. She would cut the leaves of the chrysanthemums, put the button hook at the end and pull it down the leaf to make it crinkle.

For our Christmas dinner in 1926, the man next door, who was employed by the gas works, gave us half of his beef joint, as he was better off than us. With her paper flower money, Mum was able to buy the fruit for our Christmas pudding. I remember taking all the stones out of the sultanas - it made my fingers really sore!

The following year, Dad started up his own decorating business - ‘E. Turner - The People’s Decorator’ - and then he joined his brother-in-law, Fred, as a decorator in his firm, Nicholls and Sons. All their work was done at Hatch End, Pinner, where a lot of the film stars and opera singers used to live. After two years, Lipton’s offered Dad his old job back.

Edwin’s business card

Dad used to go out early at 6 o’clock in the morning. During the winter of 1926, we had what was called the silver frost. Dad knocked on our bedroom door and he said ‘Get up you girls! You’ve got to slide to work this morning.’ He told us to put old socks on our shoes to enable our feet to grip better on the pavements. He said ‘Keep going at a trot and you won’t fall over.’ We did this and we was very lucky not to fall over, ‘cos Florrie and I also had to carry our dinners with us. We generally used to take our dinner down to our canteen at work and heat it up. I had sausage and mash in a basin under me arm and my sister had a flask as we would have a cuppa in the morning (we were never allowed to stop work for cups of tea though, just to go to the toilet). I got a fit of the giggles at work afterwards just thinking about it!

The silver frost was unbelievable - the sight outside. Everything was absolutely white - telegraph poles, everything was shining with silver. I’d never seen anything like it.

Alice, one of the twins who lived in the flat upstairs, worked at Waterlows in London, where they used to make the banknotes. Alice and Dad caught the same train from St. James Street, Walthamstow, to Old Street, London, where Dad would pick up his van. They would walk up the road together.

The houses at the top of the road had five stone steps and, as they walked by, a woman opened her front door and came down the steps to the gate to fetch the milk (that’s when we used to have three milk deliveries a day, if we wanted it!) As she did so, she slipped on the icy steps and her nightdress went up over her head. Alice covered her eyes when Dad said ‘Don’t look Alice!’ He went and helped the woman up and pulled her nightdress back down again. I can always remember him telling us that. It was funny, that was!

I also remember my mother placing some small sheets of glass over tiles in the kitchen and smoking the glass by holding a candle over them. This was to protect our eyes whilst watching the total eclipse in 1927.’

Ten

Friends, Fun and Frolics

When Ethel was about 17, she had an encounter with a pet blackbird, which her paternal grandfather once found on his allotment:

‘My grandfather used to go down to the allotment and pick young fresh dandelion leaves to use as lettuce. He never bought lettuce. ‘Dandelion leaves are much better than lettuce,’ he said. He hardly ever ate fried eggs either. When he used to fry a bit of bacon, he used apple rings instead of eggs to go with it. That was his breakfast on Sunday mornings.

Anyway, one morning, he discovered a young blackbird on the allotment. It had obviously been abandoned, so he took it home with him and looked after it until it got bigger. As he didn’t like keeping

it in a cage in his flat, he gave it to my Dad. The bird wouldn’t have lived in the wild again, ‘cos it was so tame. My Dad hung the cage outside by the brick wall of the outside toilet in the summer and used to take it inside in the winter. One autumn, I’d gathered a lot of blackberries to make some wine with. I’d strained them and was going to strain them again that night. I was wearing a nice cream linen dress for work and the wine was on the table covered with a bit of muslin. The blackbird’s cage had been brought into the kitchen, because it was getting cold, and Dad had given the bird a snail to eat, which it did using the stone in its cage to crack open the shell.

While I was seeing to the wine, Mum warned me to watch out for flying bits of snail shell. As I got up on a stool to look inside the cage, it came off its hook into my arms and I fell backwards tipping the bowl of blackberry wine all over me head and me lovely linen dress! Luckily Mum managed to get all the stain out by soaking the dress in salt water in her old copper!’

Ethel in the 1920s

Another amusing incident occurred one night, when, as a young woman in the 1920’s, Ethel had been ‘out on the razzle’ with some friends:

‘I remember ever so clearly - I’d been out and got in at 10 o’clock, ‘cos you went to bed early then, when you’d been working hard, and this night, Mum and Dad had gone to bed.

Dad never used to turn his light out, he used to sit there with his watch - ‘See the time, you’re a minute late,’ he used to say. Anyway, I went into the bedroom and switched my light on … we had those casement windows, you know, and mine was open a little bit to let in the fresh air (it was summer time, see). Well, what happened was, I pulled the bedclothes back to get in and there was this spider. I’ve never seen one so big in all my life and I’m not exaggerating. Its legs were huge and they was all hairy! I screamed and pushed the bedclothes back. Now I don’t dislike spiders and I really don’t like to kill ‘em, but I couldn’t touch that one, it was massive; it must have been a foreign one come over in a box of bananas delivered to the grocer’s at the top of Edward Road. I flew into Mum and Dad’s room calling ‘Dad! Dad! Quick!!’

Now, my Dad used to wear those old-fashioned shirts with the collar attached (I used to ‘ave to scrub ‘em) and they always had long back tails. He always went to bed in ‘is shirt and my parents’ bed was one of those on the old-fashioned wooden frames with the springs. My Mum was rather on the plump side and used to sleep against the wall. Me Dad jumped out of bed so quick and me poor ol’ Mum was tipped into the corner!

Suddenly realising that he’d only got his shirt on, me Dad pulled the tail of it between his legs to hide his privates - and I’ve never forgotten the way he ran down the hallway, it was so funny! My Mum had a good sense of humour and I can laugh too. It’s a good job I can, what with some of the things I’ve been through!

Anyway, when Dad came out of my room, he said that he’d knocked the spider to the floor with his slipper and crushed it. Honest to God, it had black hairs on its legs and was that size. It certainly frightened the life out of me and my Dad, and we don’t scare easy!’

Ethel holding her certificate pronouncing her a life governor of the Connaught Hospital

Ethel’s great sense of humour and fun was also to be put to good use raising money for charity, in particular, for the Connaught Hospital, of which she became a Life Governor in 1939. With her late friend Doris, Ethel used to parade in Walthamstow Carnival each year:

‘The first year Doris dressed up as a soldier and I went as an English lady in a petticoat (I showed me knickers!). I also wore a crinoline bonnet and carried a parasol. I must have been 19 or 20 then. The following year, I was a Spanish man complete with black hat, jacket and mandolin and for the final time, Doris and I entered as the Bisto Kids. We sent away for the clothes for that, but we had to find our own shoes. They sent us the wigs and everything. I made a sawdust pie with pastry on top and stuck wire in it with cotton wool on top to look like smoke. And we won second prize! Doris’s nephew had a little barrow. Doris asked if we could borrow it to push me up to the podium to collect our prizes. It was so small, I couldn’t get out of it afterwards, ‘cos me hips stuck!! The other funny thing was, we won a camera from Ensign, where I had worked since I was 14!’

Ethel and friend Doris at subsequent Walthamstow carnivals

Ethel and Doris got up to many more pranks with their friends and colleagues when they went on their many days out together before the start of the Second World War:

‘When us girls had our Sundays out, we used to go sometimes to the Kursaal at Southend. If there happened to be a ride that hadn’t attracted many people, Doris used to ask the attendant to let us girls go on for half fare in return for shoutin’ and hollerin’ a bit to attract more trade. We used to go on those rides where your skirts blew up, like on the Big Wheel. We thought it was real funny. We never used to wear trousers in those days, we had dresses on!

But they wouldn’t let us go on the railway thing - roller coaster, I think you’d call it now - ‘cos it was too expensive. Very high it was. My chap Joe, took me on it once, ‘cos I said I hadn’t been on it before, but he didn’t want to sit in the front. When our turn came, he had to sit in the front seat ‘cos it was the only one left. Joe was terrified and turned really green. When he got off, he couldn’t stand. The ride was terrific and I really enjoyed it, but I wouldn’t go on it now!

We never ‘ad much money, so we couldn’t go on a lot. Once, as we went out of the Kursaal, Doris and I got on the weighing machine together and broke it, so we ran out!

We used to travel by train on our days out. We’d pick the tram up at the top of the turning, where the market was in Walthamstow, and travelled to Stratford to board the train. That was when we were going to Walton-on-the-Naze. But when we went to Southend, I used to walk to the Blackhorse Road to catch the train. London, Midland and Scottish (LMS) was the name of the railway company, and it took you right into Southend.

Anyway, when we travelled to Walton, I crocheted hats for all of us and sewed a white feather on the top. Then, when we were riding on the top of the tram to Stratford, we would be able to see the members of our crowd. I used to say ‘There’s another one - she’s got a white feather in her hat!’ If we lost someone coming home, I’d know because there’d be a white feather missing when I’d counted them all. There were usually 24 of us, you see. And, do you know - I remember every one. One used to do the bookwork for the convent school for the poor kids. She was a good person, she was.

Coming back once from a trip to the seaside, Doris was saying how hungry she felt. We got in a carriage that had a little side toilet to it. As there was no light in the main carriage, we put the light on in the cubicle and left the door open. Our manager’s secretary - I’ll never forget her, she was so la-di-da - wanted to come with us. None of us liked her very much, especially Doris, ‘cos she was so stuck up. Well, as Doris was hungry, she decided to eat this hard-boiled egg she had with her, but just as she was about to put it into her mouth, this girl yawned. Doris saw her opportunity and, in the dim light of the carriage, threw the egg at her. ‘How disgusting!’ the girl said. That started us all off and we had this amazing food fight with everything we had in our bags! Then, just before we got to Stratford, we cleared up the carriage - the windows, everything. We never did no damage, we just used to have some good fun, you know!

In the winter, when we couldn’t go to the seaside, we used to go up to London, to the theatre. My friend, Joan, who was the manager of a nice shop in London (I’ve still got a nice pair of scissors from there) said that if ever we wanted to go to the theatre, we were to inform her and she would book us our tickets for sixpence… We used to go to work on a Friday and our foreman used to say ‘Where you goin’ tonight girls?’ After work, we’d walk up Wood Street, near Forest Road, all of us together, and catch the train to go to the theatre. We’d make sure that our seats were booked, then go to the large Lyons Corner House to have something to eat like fish ‘n’ chips

.

We saw some lovely shows. I remember there being one show with nude people in it, but we wouldn’t go to that one! We did see Dulcie Gray and her husband (Michael Denison) once and we did go to the White Horse theatre a couple of times too. As there were a lot of us, we got in a bit cheaper. We was artful then, but we didn’t ‘ave much pocket money, see. I didn’t earn my full wages of 28 shillings a week ‘til I was 21. I started on eight shillings a week and, until I came of age, I received tuppence an hour more each birthday. I worked from eight o’clock until half past five, Saturdays ‘til half past 12, and you weren’t allowed to leave until you’d made sure that your desk was all clean and tidy ready for Monday.

We was goin’ up to Wood Street to catch the train once, when Doris bought some stink bombs and jumping crackers from a shop near the station. She said that when we went through the tunnel at Hackney Downs Station, we’d let these crackers off in the train. She told me to sit on one side of the door and she would sit on the other. When it all went dark in the tunnel, we let the crackers off. The girls screeched and, when the train had passed through and it was light again, I saw that one girl was hanging onto the luggage rack! A jumping cracker had burnt a hole in her coat. Were we sorry, but we still chucked the two stink bombs into the carriage just as we got out at Liverpool Street! I tell you, that snobby girl never came with us again!

Doris was the one who suggested all those pranks, not me. And there was another one called May - she was just as mad. May was a lovely person, a real tomboy. She was six feet tall and full of life and fun. Whenever you went out with May and Doris, you knew you were going to have a good time. I used to do all the organising and they used to arrange all the fun.

Jellied Eels and Zeppelins

Jellied Eels and Zeppelins